The finding alters the understanding of Venus’ atmosphere that has prevailed for decades.

Data fortuitously collected by NASA’s MESSENGER mission reveals a surge in nitrogen concentrations 45 kilometers above the surface of Venus, demonstrating that the planet’s atmosphere is not uniformly mixed, as scientists maintained until now.

The finding alters the understanding of Venus’ atmosphere that has prevailed for decades. The study is published in the April 20 issue of Nature Astronomy. Despite the fact that the discovery was published recently, the background story can be traced back to June 2007 when MESSENGER (Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry, and Ranging) flew over Venus before diverting to Mercury, where it completed a ten-year research mission.

The mission’s instrument teams took the opportunity to test their devices and collect data before the actual show began about six months later.

Among the team members was David Lawrence, a nuclear physicist at the APL (Applied Physical Laboratory) at Johns Hopkins University. He was the scientist for the MESSENGER neutron spectrometer instrument, which detected neutrons released into space by cosmic rays that collide with molecules in the atmosphere or surface of a planet.

Their goal was to find telltale signs of neutrons coming from hydrogen atoms in water molecules that were suspected (and later confirmed) to be frozen in the crater shadows at Mercury’s poles.

However, on Venus, Lawrence just wanted to collect some data to verify that the instrument was working properly. An initial check showed it worked, and the data was presented. But in 2010, Lawrence reviewed those measurements, this time with Patrick Peplowski, another APL nuclear physicist. Despite 50 years of sending robotic missions to Venus, including 13 atmospheric probes or landers, great uncertainty remained about the concentration of nitrogen in Venus’ atmosphere, especially between 30 and 60 miles above the surface.

That puzzled Peplowski and Lawrence because nitrogen is the second most abundant molecule that floats in Venus’ atmosphere, after carbon dioxide.

“The uncertainty wasn’t necessarily just in the MESSENGER instrument — it could be in the entire planet,” Lawrence said in a statement.

Lawrence knew of a 1962 article that suggested that neutron spectroscopy could help determine the atmospheric nitrogen concentration of Venus. Nitrogen is good enough at removing loose neutrons, unlike carbon and oxygen, which are some of the worst. So on Venus, the number of neutrons an instrument detects must depend on the amount of atmospheric nitrogen. MESSENGER collected that information.

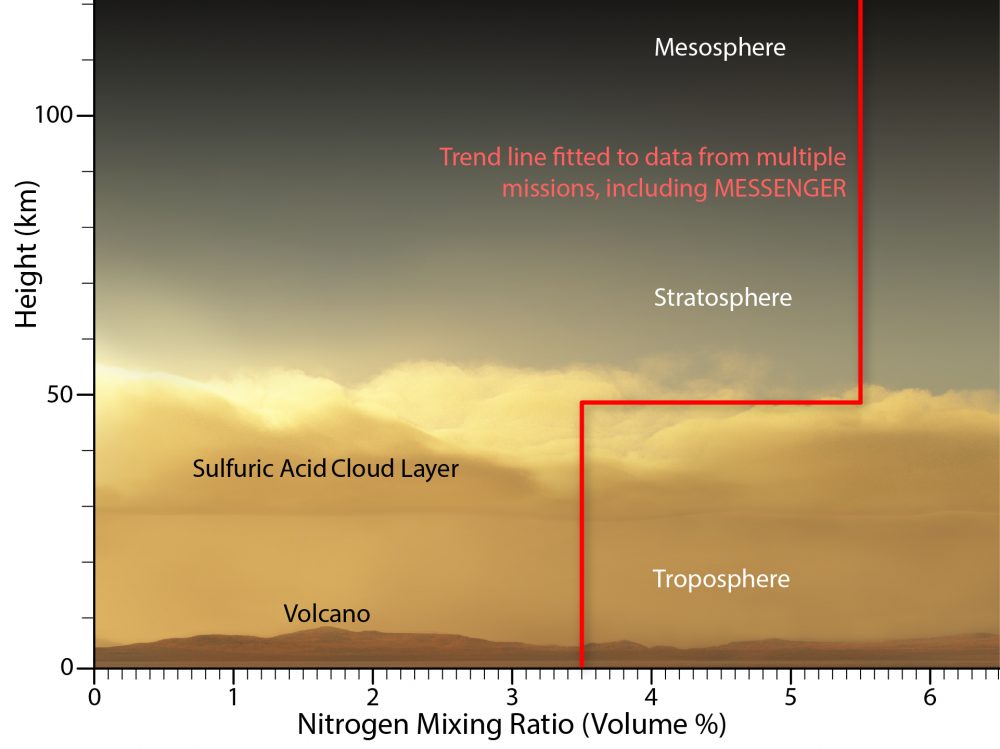

The researchers performed a computer simulation that divided the planet’s 90-kilometer-thick atmosphere into bands in which they could manipulate the nitrogen concentration and realistically model how many neutrons would come out of the spacecraft.

When they compared their models with the MESSENGER data, they found that the best match was when atmospheric nitrogen represented 5% of the volume, about 1.5 times the lowest measured in the atmosphere. And all the neutrons came from a region about 50 to 90 kilometers above the surface, exactly where there had been the greatest uncertainty.

“That was a stroke of luck,” said Peplowski.

The exact reason as to why nitrogen seems to increase at higher altitudes remains a Venusian enigma. Nonetheless, their findings raised several eyebrows, but not because people were blown away. In fact, many colleagues seemed rather surprised that this was something even worth investigating.

“The notion that there’s a higher nitrogen concentration in the upper atmosphere than in the lower was outside people’s range of thought.”

They ran into that obstacle earlier when trying to raise funds to complete the study. The project was denied money three times because it was considered a dead end. The data they needed to feel confident in their results and bring their study to the goal luckily came through Jack Wilson, an APL scientist who was analyzing the same MESSENGER data for an unrelated project. After the team presented preliminary results during a conference in 2016, the Russian Federal Space Agency cited their work on their Venera-D mission to study the atmosphere and surface of Venus.

Currently, two mission proposals under consideration for NASA’s Discovery Program, DAVINCI + and VERITAS, which include APL scientists on their teams, also aim to study the atmosphere of Venus in greater detail.

Peplowski and Lawrence say this new result underscores the caution researchers need when drawing conclusions about atmospheric data, especially with the growing interest in planetary atmospheres in other solar systems.

“We are still learning fundamental things about Venus and its atmosphere, and it is our next-door neighbor,” Peplowski said. “It is worth questioning that scientists can confidently speak about the atmospheres of exoplanets that are hundreds or thousands of light-years away.”

Drawing rigorous and compelling conclusions requires a wide range of data. But getting that data can sometimes take just a little bit of good luck.