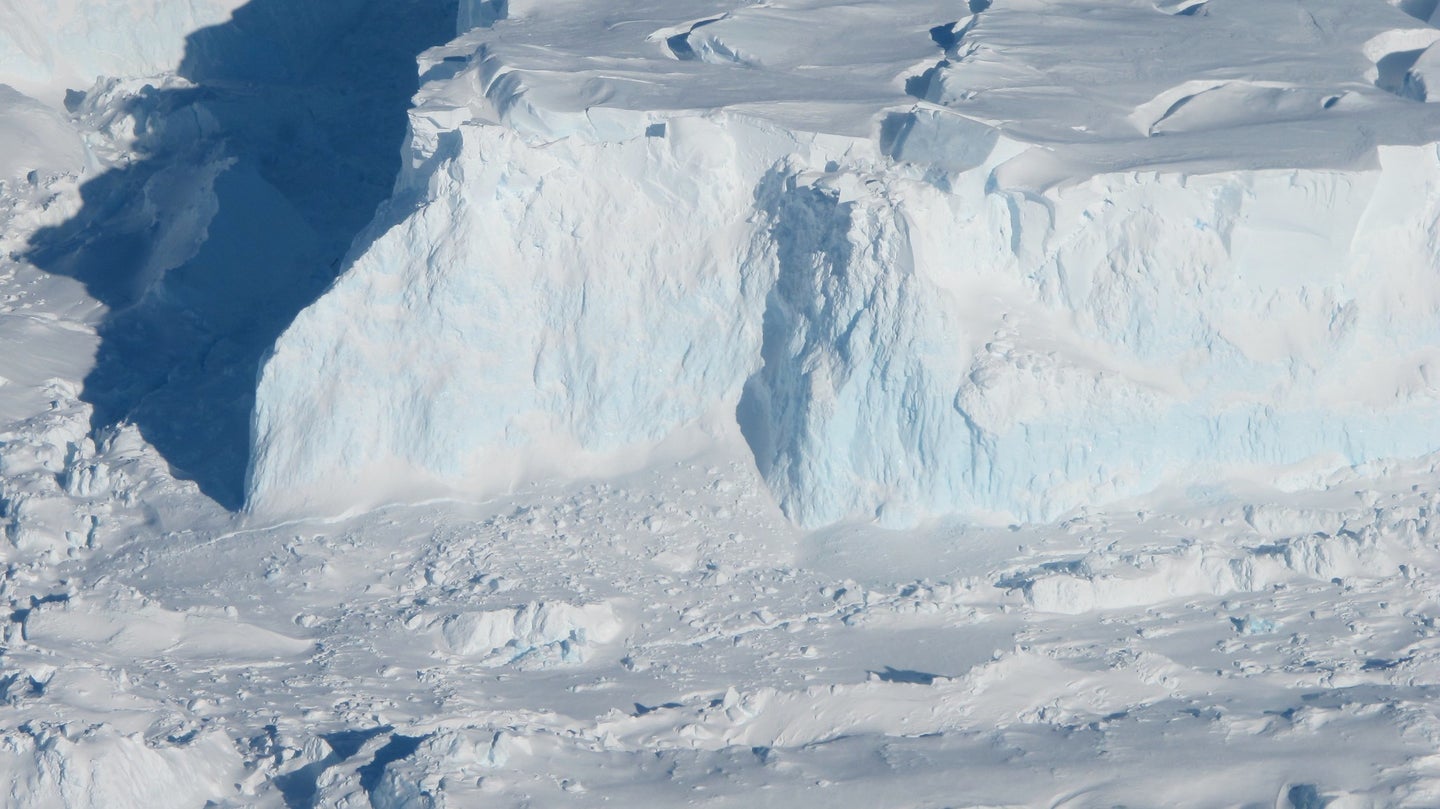

One of the ever-looming threats of climate change is sea level rise, which already threatens to displace millions of people worldwide and force them to move inland by the end of the century. A big part of the rising water levels are hotter temperatures at the poles—home to giant glaciers and ice shelves that hold crucial quantities of frozen H2O.

The Florida-sized Thwaites glacier in Antarctica, nicknamed the “doomsday glacier,” is already losing 50 billion tons of ice each year. That in itself accounts for around 4 percent of annual global sea level rise. But unpublished research shared at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting this week shows that the thinning ice shelf extending from Thwaites could shatter within the next three to five years. Behind Thwaites lies an even larger body of ice that, if the glacier melts, will be exposed to increasingly warm waters.

“Thwaites is the widest glacier in the world,” Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and lead coordinator for the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), said in a press release. “It’s doubled its outflow speed within the last 30 years, and the glacier in its entirety holds enough water to raise [global] sea levels by over two feet. And it could lead to even more sea level rise, up to 10 feet, if it draws the surrounding glaciers with it.”

[Related: Ice sheets can melt much faster than we thought]

Thwaites has been in trouble for a while now—and scientists have been trying to figure out how exactly climate change will impact the rate of melting on it and other vulnerable glaciers. These new insights, however, show that the warming Southern Ocean is melting the ice from below, forming large cracks across the floating ice shelf.

“I visualize it somewhat similar to that car window where you have a few cracks that are slowly propagating, and then suddenly you go over a bump in your car and the whole thing just starts to shatter in every direction,” Erin Pettit, a glaciologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis, said at the meeting on December 13.

The ice shelf is a floating part of the glacier held steady by an “underwater mountain,” according to the CIRES release. If cracked, it’s only a matter of time until all that ice can melt and rush into the ocean. “What’s most concerning about the recent results is that it’s pointing to a collapse of this ice shelf, this kind of safety band that holds the ice on the land,” Peter Davis, oceanographer with the British Antarctic Survey, told CNN. “If we lose this ice shelf, then the glacier will flow into the ocean more quickly, contributing towards sea level rise.”

Warming water creeping underneath the glacier also causes the ice to lose its grip on the “grounding zone”—the section of seabed holding the glacier in place. Peter Washam, a research associate at Cornell University, discovered through a remote-controlled underwater robot that the grounding floor is in “chaotic” shape due to warm water, rugged ice, and a steeply sloped base. Tides additionally pump warm water between the bedrock and the glacier, further impacting stability.

“If Thwaites were to collapse, it would drag most of West Antarctica’s ice with it,” Scambos said in the release. “So it’s critical to get a clearer picture of how the glacier will behave over the next 100 years.” Research from the ITGC, a group of 100 scientists making up the largest UK-US project on the southern continent in 70 years, will continue surveying Thwaites’s shaky future.